John Tornow was born on September 4, 1880, into a respected homesteading family near the Satsop River in Washington. From childhood, he preferred the wilderness to human company, spending long hours roaming the forests and befriending wild animals rather than other children.

At ten years old, a family incident changed him forever: when his brother Ed killed his beloved dog, John retaliated by killing Ed’s in return. From then on, he withdrew further from people, often disappearing into the woods for weeks.

Living off the land, Tornow became a master tracker and an extraordinary marksman, rivaling the Native hunters of the region. By his teenage years, animals approached him without fear, and his family began to whisper that he was “not quite right.”

Though his brothers built a logging business, John only worked with them occasionally, preferring solitude in the forest. Dressed in skins, bark shoes, and towering at 6’4” and nearly 250 pounds, he cut an intimidating figure. Most saw him as eccentric, but harmless.

By the early 1900s, however, his presence unsettled people. He sometimes watched loggers at work, warning them: “I’ll kill anyone who comes after me. These are my woods.” Convinced of his madness, his brothers committed him to a sanitarium in Oregon in 1909. A year later, he escaped and vanished back into the forest.

The Murders of the Bauer Twins

For more than a year, Tornow lived unseen, occasionally visiting his sister and her twin sons, John and Will Bauer, though he refused contact with his brothers. By then, stories were spreading of a hairy, gorilla-like man haunting the woods.

In September 1911, Tornow shot a cow near his sister’s cabin. While dressing the carcass, he came under fire. He returned shots and, investigating, found his 19-year-old nephews dead. Some believed the boys mistook him for a bear, while others claimed they deliberately targeted him. Either way, Tornow fled into the dense Wynoochee Valley, and the legend began.

Deputy Sheriff John McKenzie soon organized a posse of 50 men. Though they scoured the valleys, Tornow’s uncanny ability to vanish kept him free. Fear grew, and tales of the “Wild Man of the Wynoochee,” “Cougar Man,” and “Mad Daniel Boone” spread through nearby towns. Families locked doors, armed themselves, and warned children to stay indoors.

The Crime Spree and Growing Manhunt

That winter, Tornow survived by raiding cabins and stores. In one burglary, he accidentally stole a strongbox containing $15,000 from Jackson’s Country Grocery, which also served as a bank. A $1,000 reward was posted, drawing even more hunters into the search. The fear was so great that in February 1912, a hunter killed a 17-year-old boy, mistaking him for Tornow.

In March, Sheriff McKenzie and Game Warden Albert Elmer pursued a lead at Oxbow but never returned. Their bodies were later found—shot between the eyes and mutilated. The bounty doubled to $2,000, and more posses scoured the forest, yet Tornow remained elusive.

Final Encounter and Death

On April 16, 1912, Deputy Giles Quimby and two companions discovered a rough bark shack they believed was Tornow’s hideout. A gunfight erupted. Louis Blair was wounded, Charlie Lathrop killed instantly, and Quimby found himself negotiating alone with the fugitive.

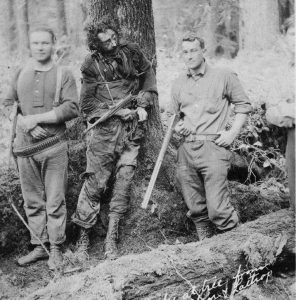

Tornow shouted that the stolen money was buried in Oxbow near a boulder shaped like a fish’s fin. Quimby promised to leave him in peace if he revealed the location. But after Tornow complied, Quimby opened fire. Later that day, a larger posse returned and found Tornow dead, slumped against a tree with a few silver coins on him.

Aftermath and Legend

News of his death spread instantly. In Montesano, crowds swarmed the morgue to see his body; nearly 700 people demanded a glimpse, forcing deputies to guard against souvenir hunters tearing pieces from his clothing. His brother Fred lamented that death was better than a prison cell.

Deputy Quimby, hailed as a hero, refused offers to tour on stage telling the tale. Meanwhile, treasure hunters scoured Oxbow for decades seeking the missing $15,000 strongbox, but it was never found. Some believe it still lies buried near the Wynoochee River, altered by the later construction of a dam.

John Tornow was laid to rest in Matlock Cemetery, where his grave remains. His story endures in Washington folklore: part outlaw tale, part wilderness myth, and a chilling reminder of how fear can turn a man into a legend.

A postcard captioned, “Tornow’s Body at tree from which he shot Blair and Lathrop”. Two men with rifles pose, one on each side of Tornow’s corpse, in whose dead arms they have propped a rifle. The man standing on the left is wearing an ammunition belt around his waist. C.H. Packard, Hoquiam Polson Museum

A postcard captioned, “Tornow’s Body at tree from which he shot Blair and Lathrop”. Two men with rifles pose, one on each side of Tornow’s corpse, in whose dead arms they have propped a rifle. The man standing on the left is wearing an ammunition belt around his waist. C.H. Packard, Hoquiam Polson Museum

Tornow’s legacy remains debated: was he a deranged killer or a misunderstood loner? A 2014 historical novel, John Tornow: Villain or Victim? by Bill Lindstrom, explores this question, suggesting conspiracy theories and local accounts paint a complex picture. A stone monument in the Wynoochee Valley commemorates him and two victims, inscribed with “Friend or foe, we’ll never know.” His story also inspired a 2024 musical, Wild Man of the Wynoochee, performed in Port Townsend.

sourced – Historypedia —